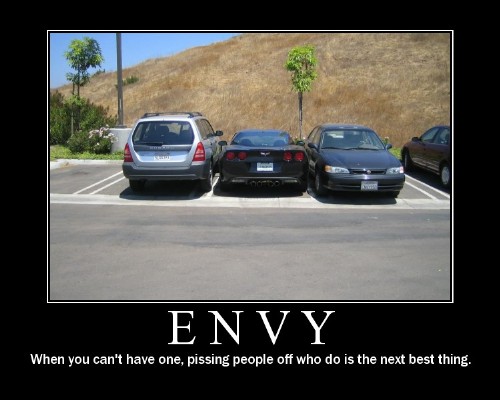

NOTHING GOOD EVER COMES OUT OF TRYING TO KEEP UP MATERIALISTICALLY WITH ONE'S NEIGHBORS.

This point is illustrated when Pecola finally gets blue eyes. Instead of being satisfied, she can’t stop from asking if they are “prettier than Joanna’s”[3] and “bluer than Michelena’s”[4]; her reply to the responses of “yes” is simply and self-consciously, “are you sure?” [5]There is the constant thirst to make more money, so that one can have more things, so that one can somehow be dominant over their neighbors. It is a never-ending cycle that ultimately leaves its victims unquenched.

CONSUMERISM: THE ANTI-GATORADE.

However, materialism is not the only negative obsession in America.

There is a constant quest by both male and female to achieve a cookie-cutter type of beauty, one that is fed to our population by every source of media: television, music, magazines, and the Internet. Our senses are constantly bombarded with people who we are told look beautiful; we inevitably begin to feel as if one must look like these people—these movie stars, athletes, musicians—if we too are to be considered beautiful. Toni Morrison notices this trend in culture, and tells it through the eyes of “an ugly little girl asking for beauty.”[6] “The Bluest Eye focuses on how what Morrison called the ‘universal’ love of ideal beauty commodified in such dolls enforced by the ‘glazed separateness’ that Pecola saw.”[7] Pecola wants to be beautiful and have blue eyes like the dolls she plays with and white girls, just as people in our society “look in the mirror and see that they are not as beautiful as a movie star, not as beautiful as the television, magazine, and billboard ads tell them they should be, they feel the fear of rejection and abandonment.”[8]

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NDBpavNnPWY&feature=related

"IS THAT WHAT A MAN LOOKS LIKE?"

This idea of wanting to look like famous people brings to mind an MTV show that was on the air while I was in high school called “I Want a Famous Face.” The subject of the show was true to the title—it documented the story of people who wanted to resemble or have the same features of someone famous, and they got plastic surgery to achieve this.

TWO PARTICIPANTS ON "I WANT A FAMOUS FACE." THEY WANTED TO LOOK LIKE BRAD PITT.

Ironically, about half of the time they ended up looking completely ridiculous and unnatural; there were also always short segments on the show about plastic surgery gone wrong. This show completely encapsulated our society’s obsession with achieving a standard of beauty, to the point that they would be willing to mutilate their bodies to achieve it.

This obsession can’t possibly continue if people are to have any sense of self-esteem. Plus without all thousand dollar makeup artists and hair stylists, famous people aren’t that attractive.

CASE IN POINT.